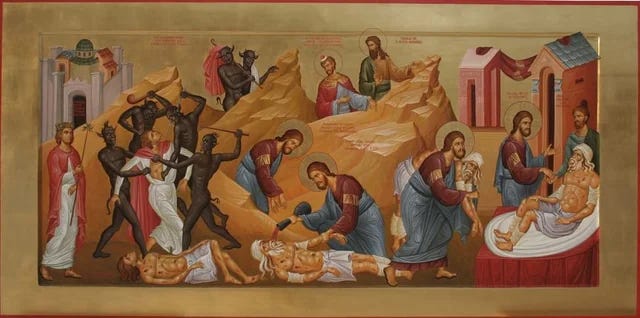

If iconography is anything to go by it appears to be universally accepted that Christ is the Good Samaritan in the famous parable from Luke 10 that will be read in churches across the world this weekend (Proper 10). To be clear, I’m not opposed to Christ as the Good Samaritan. But I think we need to be careful of overly tight readings of parables.

Parables are not allegories. They don’t always have A to B equivalence. That is to say, by way of example, in the Narnia stories Aslan is the Christ-figure in the same way that Lucy isn’t. Parables reward thinking sideways. If Narnia was a parable we would do well to ask, “What might we learn if Lucy was read as a Christ figure in the story?”

Parables invite us to listen (Let the one who has ears hear), to ponder, to look at things obtusely. Which is what I want to encourage us to do about the Good Samaritan. Particularly because I think the lead up to this story invites us, at very least, to consider it.

Here’s my question: What if Christ was the victim in the story of the Good Samaritan?

Whenever we read the Good Samaritan I think we intuitively know, and the conclusion confirms for us, that we need to imitate Christ’s behaviour in the story. If Christ is the Samaritan it allows us effortlessly to jump to the conclusion that Christ is calling us to help, to fix, and to sort out. Irregardless of whether or not we are any good at these things, we like the idea that these are the things we should do. I am not trying to say this cynically, but this particular reading of the parable activates our inner “saviour complex” which is now boosted into a “Jesus-imitating, saviour complex”. Obviously this requires caution. Anne Lamott reminds us in Almost Everything: Notes on Hope:

“Help is the sunny side of control.”

So I want to attempt a different way of reading the text. Not because I have a problem with Christ as the Good Samaritan, but because I want to temper that sense of “saviour” in us. This is not a claim to be a better reading, just a different one. Leaning into the possibility of the parable. Maybe we just call it another reading.

How did we get to where we are?

Whether you are tracking the Lectionary in Ordinary Time or reading Luke’s Gospel sequentially there’s a subtle pattern to follow. Jesus is rejected by the village after his engagement with the demon Legion (Luke 8:26-39). He is set on going to Jerusalem in Luke 9 but is rejected by none other than Samaritans in verses 51-56, leading James and John to suggest that they sort things out in a somewhat incendiary manner. Immediately following this, in Luke 10:1-11, he sends out seventy-two disciples (presumably somewhere other than Jerusalem) with “no purse, no bag, no sandals” and the instruction to “greet no one on the road”. Significantly, as I posted elsewhere, he sends them out on mission in a way that requires them to accept hospitality. The mission insists they be guests of the people of peace they encounter (10:5-7). This is not a commission of power or control, but of Christ-imitating presence. It’s difficult not to see the cruciformity1 of this; the subtly that Christ saves not by power but by humility.

A Sideways Approach to the Good Samaritan

So with that in mind, read the Parable of the Good Samaritan again. It comes only a few verses after the sequence we’ve just traced, in Luke 10:25-37. Following the trail, here’s my sideways reading.

Jesus is asked a question about theology that very quickly becomes a question about hospitality. “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” quickly becomes “Who is my neighbour?” Jesus retorts with a tale of a man going away from Jerusalem, not dissimilat to the Seventy-Two disciples. He is set upon by bandits (curiously, they are lēstēs. Curious becaus Jesus is later crucified alongside two lēstēs) who leave him, and I’m being playful here, with no purse, no bag, no sandals (cf. 10:4). Continuing my fun, forgive me, notice that a priest and a levite now pass by without “greeting him on the road” (again cf. 10:4).

Does St. Luke want us to imagine a comparison between the disciples sent out on mission and this man in the parable?

Now help comes and shockingly for the crowd, but perhaps also for us, it’s a Samaritan. Yes, someone from that group that refused Jesus hospitality just a few verses ago (9:52-53). The Samaritan offers the traveller care, sustenance, and hospitality, at his own expense.

Another question. Is the Samaritan not exactly the type of person Jesus told the Seventy-Two to be on the search for? Is the Samaritan not a person of peace?

He [the Lord] teaches that the man going down was the neighbour of no one except of him who wanted to keep the commandments and prepare himself to be a neighbour to every one that needs help. This is what is found after the end of the parable, “Which of these three does it seem to you is the neighbour of the man who fell among robbers?” Neither the priest nor the Levite was his neighbour, but—as the teacher of the law himself answered—“he who showed pity” was his neighbour. The Saviour says, “Go, and do likewise.”

- Origen, Homilies on the Gospel of Luke (34.2.9)

In my post Incarnation, Eden, & Hospitality I argued that everything Jesus asks the Seventy-Two to do he also does himself. He is the model for them to imitate. Which leads me to wonder how outlandish it might be to suggest that Christ is not only the victim in the story, but is encouraging his disciples to see themselves in the same way.

I realize that this is reading against the grain of how many of us have learned this parable. However, as I said above, I do think we need to be cautious of our saviour complex, especially in light of how Jesus sends the disciples on mission. They are sent out in lack. They do not have all they need. They need to be cared for. They can only be successful if they encounter people of peace willing to show hospitality. The mission will only succeed if they meet people like this Samaritan. A person of peace amidst a people who have not welcomed Jesus.

Fortunately I’m not alone in seeing Jesus as the traveller. Having sketched some of this out, I grabbed Robert Farrar Capon’s Kingdom, Grace, and Judgment and noticed his comment on our parable. Arguing that it is those suffering and dying who look most like Christ he says:

The actual Christ-figure in the story, therefore, is yet another loser, yet another down-and-outer who, by just lying there in his lostness and proximity to death (hēmithanḗ, “practically dead,” is the way Jesus describes him), is in fact the closest thing to Jesus in the parable.2

Capon continues to argue that the parable is misnamed, citing similar concerns to mine:

Calling it the Good Samaritan inevitably sets up its hearers to take it as a story whose hero offers them a good example for imitation. I am, of course, aware of the fact that Jesus ends the parable precisely on the note of imitation: “You, too, go and do likewise.” But the common, good-works interpretation of the imitation to which Jesus invites us all too easily gives the Gospel a fast shuffle. True enough, we are called to imitation. But imitation of what, exactly? Is it not the imitatio Christi, the following of Jesus? And is not that following of him far more than just a matter of doing kind acts? Is it not the following of him into the only mystery that can save the world, namely, his passion, death, and resurrection? Is it not, tout court, the taking up of his cross?3

Mission as Humility

Continuing to build on what I said in Incarnation, Eden, & Hospitality, the invitation of God has always been for us to be guests in his creation. The call of the disciples at the start of Luke 10 was to go and model this as mission. Jesus doesn’t envisage his mission as a quest for control and ownership, but to reconcile us as God’s guests. The disciple of Jesus then models this by also being a guest in the house of the other. The mission of the Kingdom of God is to model the vision of Eden where we were the guests in God’s garden and at his table.

So in a missiological-sideways reading we can argue that, in the parable the incarnate-Christ-imitating, traveller-missionary going out from Jerusalem (cf. Luke 24:47, Acts 1:8?) is found in need of hospitality, just as Jesus said his disciples would. The traveller’s weakness then becomes the “mechanism” that brings “Christ” into the house of another. The Samaritan is Christ’s person of peace, in the house of peace, amongst the people who refused to welcome him.

Who was neighbourly?

Jesus’s concluding question to the expert is worthy of our attention. English translations sometimes imply that Jesus asks an identity question, “Who was a neighbour to the man?” The Greek text, however, gives us a behavioural question, “Who was neighbourly to the man"?” The Greek tradition leans into the hospitality question and again this is instructive for us.

If we read the parable the way I have proposed in this post, we could suggest that the invitation to the expert is not to go out and practice his newly discovered saviour complex, but rather that the “do likewise” is an invitation to be a person of peace and receive Christ and/or his disciples.

If you were willing to go with me on this take on the Parable of the Good Victim, notice then that Jesus’s parable is an answer not just to the question “Who is my neighbour?” which the expert asked in 10:29. Now the parable also answers the initial question proposed in 10:25, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?”

What must I do? Be hospitable to Jesus as he comes to us. Not in power, but in weakness. Not as an owner, but as a guest in his own creation. As a crucified one who loved us by dying for us (Galatians 2:20).4 Easy to “pass on the road” yet by hospitably taking him in we become people of peace and wholeness.

This is a term popularized by Michael Gorman, but thematically similar to ideas we find in C.S. Lewis also (continuing the Narnia theme present in this post): https://wtctheology.org.uk/theomisc/c-s-lewis-and-cruciformity/

Robert Farrar Capon, Kingdom, Grace, Judgment: Paradox, Outrage, and Vindication in the Parables of Jesus, p.212.

ibid. p.212-213

The Galatians allusion makes me want to explore the idea from this that while he is beaten, stripped, and crucified naked, we are invited to be clothed by him in baptism (Galatians 3:27).

My friend Nick Kim made this observation that I think is a helpful to think about how this reading might align elsewhere.

Nick wrote: “This piece reminds me of, and, I believe, connects with the passage in Matthew 25 about the sheep and the goats:

"Then the righteous will answer him, saying, 'Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink?And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?' And the King will answer them, 'Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me." (Matt. 25:37-40)”

I like this. Before reading it—the moment I read your reply to my comment on “Lambs Not Consumers” with your wondering about reading this parable through a hospitality lens—I thought of Capon and his reading with Jesus as the victim, and His call to the disciples and to us, toward the same. And what a hard and cruciformed call that is. Amen. This is good stuff Brosef!