Telling the Truth Truthfully

Notes on the other side of prayer

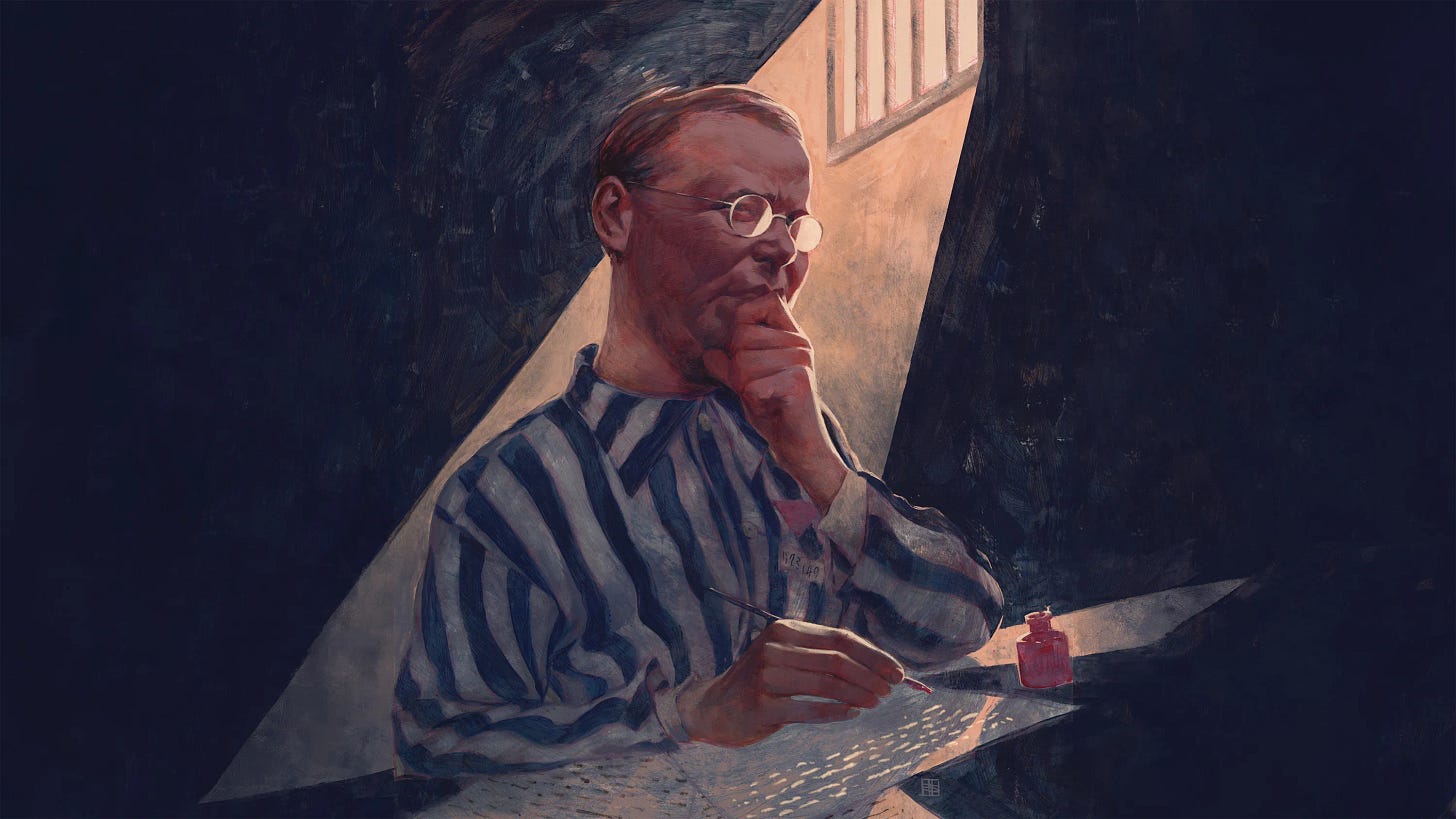

As Advent approached I shared some prayers from Dietrich Bonhoeffer that he wrote for prisoners in the midst of letters to his dear friend Eberhard Bethge. You can some of read those prayers here.

On the other side of the page from those prayers he sketched what he called a fragment of an essay. The essay traces a theme that he was conversing with his friend about via letter, clearly influenced, I would say, by being interrogated by the Nazi powers at points of his incarceration. The piece is called “What does it mean to tell the truth?” It’s a fascinating insight into how the truth can be used badly, and that while truth isn’t a thing that Bonhoeffer struggles to identify, he names the complexity of telling the truth in a way that doesn’t do evil.

A truthfulness that is not concrete is not truthful at all before God.

‘Telling the truth” is therefore not a matter only of one’s intention but also of accurate perception and of serious consideration of the real circumstances. The more diverse the life circumstances of people are, the more responsibility they have and the more difficult it is “to tell the truth.” The child, who stands in only one life relationship, namely, that with his or her parents, does not yet have anything to ponder and weigh. But already the next circle of life in which the child is placed, namely, school, brings the first difficulties. Pedagogically it is therefore of the greatest importance that in some way-not to be discussed here-the parents clarify the differences of these circles of life to their child and make his or her responsibilities understandable.

Telling the truth must therefore be learned.1

While this may initially look like Bonhoeffer is being evasive on the truth, the opposite is true. He refuses to trivialize the truth in such a way that one might hold up their hands and say, “I was just telling the truth!” as if that justifies anything they might have said.

These sentences perhaps give some context to how he thinks:

Where this word detaches itself from life and from the relationship to the concrete other person, where “the truth is told” without regard for the person to whom it is said, there it has only the appearance of truth but not its essence.

The cynic is the one who, claiming to “tell the truth” in all places and at all times and to every person in the same way, only puts on display a dead idolatrous image of the truth. By putting a halo on his own head for being a zealot for the truth who can take no account of human weaknesses, he destroys the living truth between persons.

There is such a thing as Satan’s truth. Its nature is to deny everything real under the guise of the truth.

But God’s truth judges what is created out of love; Satan’s truth judges what is created out of envy and hatred. God’s truth became flesh in the world and is alive in the real; Satan’s truth is the death of all that is real.2

Bonhoeffer then offers a masterful example that explains this complexity:

For example, a teacher asks a child in front of the class whether it is true that the child’s father often comes home drunk. This is true, but the child denies it. The teacher’s question brings the child into a situation that he or she does not yet have the maturity to handle. To be sure, the child perceives that this question is an unjustified invasion into the order of the family and must be warded off. What takes place in the family is not something that should be made known to the class. The family has its own secret that it must keep. The teacher disregards the reality of this order. In responding, the child would have to find a way to observe equally the orders of the family and those of the school. The child cannot do this yet; he or she lacks the experience, the discernment, and the capacity for appropriate expression. In flatly saying no to the teacher’s question, the response becomes untrue, to be sure; at the same time, how ever, it expresses the truth that the family is an order sui generis where the teacher was not justified to intrude. Of course, one could call the child’s answer a lie; all the same, this lie contains more truth—i.e., it corresponds more closely to the truth—than if the child had revealed the father’s weakness before the class. The child acted rightly according to the measure of the child’s perception. Yet it is the teacher alone who is guilty of the lie. By rebuking the questioner, an experienced person in the child’s situation would also have been able to avoid a formal untruth in responding and thereby would have been able to find the “right word” in the situation. Lies on the part of children and inexperienced persons in general can frequently be traced back to their being placed in situations that they cannot fully fathom. For this reason it is questionable whether it makes sense to generalize and extend the concept of lying (which is and ought to be understood as something downright reprehensible) in such a way that it coincides with the concept of a formally untrue statement. Indeed, all of this demonstrates how difficult it is to say what lying really is.3

I leave it with you to ponder.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Conspiracy and Imprisonment: 1940-1945 DBWE 16, p.603

ibid. p.604-605

ibid. p.606

Interesting example - the alcoholic family. We learn that it's best "we don't speak, don't tell". Absorbing the lie, and the pain that comes from that. Kids learn that really quick - it is amazing how many social rules are imparted on kids, then we are shocked that they end up lying.